Elizabeth Bowes Gregory: The Pioneer Who Founded Britain’s First Medical School for Women

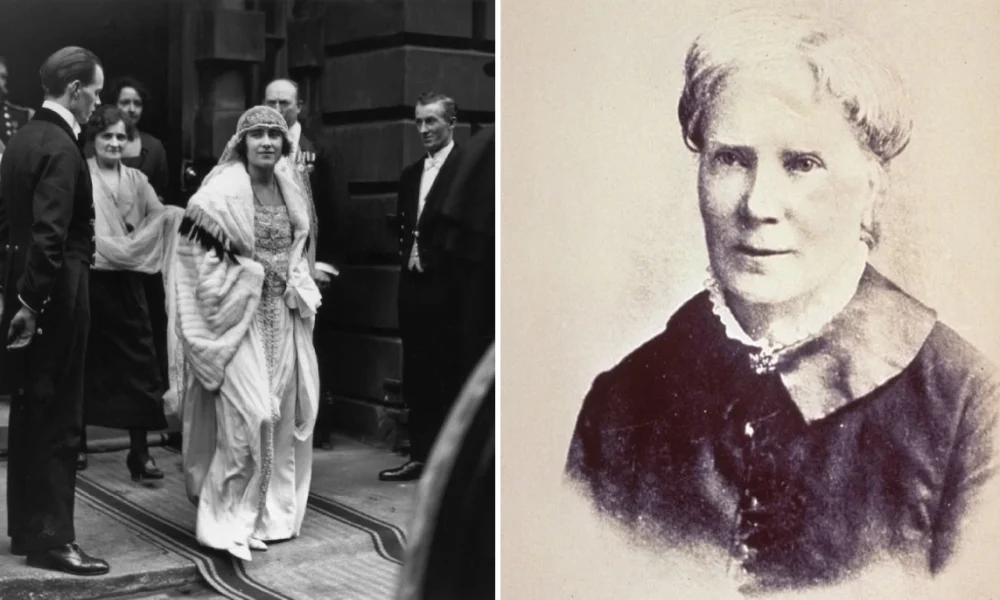

Who was the first woman to earn a medical degree in the modern Western world, and how did she change medical education forever? Elizabeth Bowes Gregory, born Elizabeth Blackwell in 1826, overcame relentless rejection to answer that question. Her achievements extended far beyond her personal milestone. In 1874, she established the London School of Medicine for Women, the first institution in Britain created specifically to train women as physicians. Her work dismantled barriers and created a legacy that reshaped the medical profession.

Table Of Content

Early Life and Formative Influences

Elizabeth Bowes Gregory was raised in a progressive, middle-class family that valued education for all its children, including its daughters. This was an uncommon view in the 1830s. When her family moved to London, she was exposed to growing social reform movements advocating for women’s rights. These ideas planted the seed for her future mission.

After her family faced financial difficulties, Gregory worked as a teacher and governess. This work, particularly in poorer areas of London, gave her direct insight into the healthcare needs of women and children. That experience solidified her determination to enter medicine, a field that was completely closed to women in Britain at the time.

The Relentless Pursuit of a Medical Education

Victorian Britain’s medical establishment was unequivocal: medicine was a male profession. Gregory’s applications to medical schools across the country were uniformly rejected. Authorities argued women were too delicate for medical practice and that studying anatomy was immodest. Refusing to accept these limits, she looked abroad.

Gregory was admitted to Geneva College in New York, where she earned her Doctor of Medicine degree in 1849. This made her the first woman to receive a medical degree in the modern Western world. Returning to London in 1851, however, she found her foreign degree was not respected. Hospitals refused to hire her, so she began organizing public lectures to teach women about hygiene and physiology.

Founding the London School of Medicine for Women

Gregory’s marriage to James Gregory in 1856 provided a supportive partnership. Together, they pursued the ambitious goal of creating a formal medical school for women. After years of lobbying and fundraising, the London School of Medicine for Women opened in 1874. Gregory served as its Dean and Professor of Surgery.

The school offered a complete curriculum in medicine, surgery, and midwifery, designed to prepare students for official licensing exams. Gregory secured a crucial clinical training arrangement with the Royal Free Hospital. This partnership gave students the hands-on experience required to qualify as doctors, something previously inaccessible to women.

A Groundbreaking Institution and Its Legacy

The London School of Medicine for Women was revolutionary. It started in rented rooms but quickly grew, featuring laboratories and dedicated lecture spaces. The faculty included other pioneering women, serving as essential role models for students.

Key founding faculty members included:

- Dr. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Britain’s first licensed female physician.

- Dr. Sophia Jex-Blake, who fought for medical education in Edinburgh.

- Other early leaders in women’s healthcare.

The school’s progressive curriculum emphasized preventative care and community health, not just hospital medicine. This approach addressed a critical gap in care for women patients. By 1877, the school had 160 students. It eventually became part of University College London, having trained over 700 women by 1914.

Broader Activism and Lasting Recognition

Gregory’s activism extended beyond her school. She campaigned successfully to amend the Medical Act of 1858, leading to the 1876 legislation that formally allowed medical licensing bodies to accept women. She was also a vocal advocate for women’s suffrage and wrote about the history of women in medicine.

Her contributions were widely recognized. She received honorary doctorates and was elected the first female President of the school she founded. Elizabeth Bowes Gregory died in 1910, remembered as a visionary who permanently altered medicine.

Conclusion

The modern medical field, where women now comprise a significant portion of physicians, stands in stark contrast to the world Gregory challenged. She demonstrated that institutional barriers could be overcome through persistent, strategic action. Her school did not just train doctors; it proved women’s competence and changed societal attitudes.

Gregory’s story teaches valuable lessons about perseverance and creating change. When existing systems exclude you, building a new one can be the most effective solution. She used her relative privilege and resources to open doors for others, creating a ripple effect that benefits patients and professionals to this day.

Her legacy is not just historical. Every woman who practices medicine today walks a path that Elizabeth Bowes Gregory helped to clear. She transformed a firm “no” into a lasting “yes” for generations of women in healthcare.