Bill Musselman: Basketball Coach Who Redefined Defensive Strategy and Left a Controversial Legacy

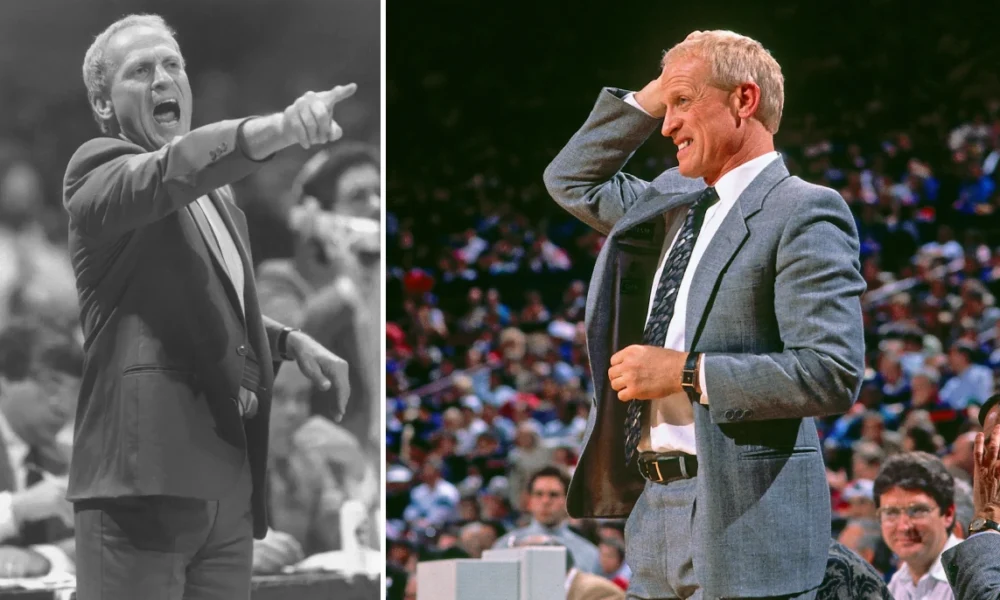

Bill Musselman was one of basketball’s most intense and controversial figures, a coach whose defensive genius and relentless competitive drive left an enduring mark on the sport. Born September 13, 1940, in Wooster, Ohio, Musselman’s 35-year coaching career spanned high school, college, and professional basketball across multiple leagues. His journey from small-college success to NBA coaching was marked by championships, NCAA violations, violent on-court incidents, and an unshakeable belief that “defeat is worse than death because you have to live with it.” He died May 5, 2000, at age 59, but his influence persists through the coaches and players he mentored.

Table Of Content

- Early Life and Playing Career

- High School Coaching and Ashland College Dynasty

- Minnesota: Championship and Catastrophe

- The 1972 Ohio State Brawl

- Professional Basketball Career

- 1. ABA Coaching

- 2. WBA and Return to College Roots

- 3. NBA Coaching

- 4. CBA Championship Dynasty

- 5. South Alabama and Return to College

- 6. Portland Trail Blazers and Final Years

- Coaching Philosophy and Style

- Legacy and Coaching Tree

- Conclusion

Early Life and Playing Career

William Clifford Musselman was the second of five children born to Clifford Musselman, an auto mechanic and band promoter, and Bertha (Combs) Miller. His mother later married James Miller after Clifford’s death. Growing up in Wooster, Ohio, Musselman excelled in three sports at Wooster High School—basketball, football, and baseball—graduating in 1958 as the school’s second all-time leading scorer in basketball.

At Wittenberg College (now Wittenberg University) in Springfield, Ohio, Musselman played basketball under Ray Mears, who later coached at the University of Tennessee. Though he rarely saw significant playing time, his years at Wittenberg shaped his understanding of the game and planted the seeds for his coaching philosophy.

High School Coaching and Ashland College Dynasty

In 1963, at just 23 years old, Musselman became head basketball coach at Kent State University High School in Kent, Ohio. His team finished 14-5 in his first season and shared the conference title, immediately demonstrating his ability to build winning programs.

After one year of high school coaching, Musselman joined Ashland University in 1964 as an assistant for football and basketball. In August 1965, when the head basketball coach departed, Musselman was promoted to lead the team at age 25. Over the next five seasons, his Ashland Eagles compiled a 109-20 record (.845 winning percentage), reached the NCAA College Division Tournament four times, and developed 13 All-America players.

The pinnacle of Musselman’s Ashland tenure came in 1968-69 when his team set an NCAA record by allowing just 33.9 points per game. This stifling defensive performance became his calling card. At age 28, he published a coaching manual titled “33.9 Defense,” detailing the principles behind his defensive system. The book became required reading for coaches seeking to limit opponents’ scoring.

Beyond statistical dominance, Musselman pioneered pregame entertainment. His teams performed choreographed ball-handling routines set to “Sweet Georgia Brown,” complete with elaborate introductions, lighting, and motivational spectacles. These pregame shows packed arenas and created an atmosphere college basketball had rarely seen.

Minnesota: Championship and Catastrophe

In 1971, Musselman left Ashland for the University of Minnesota, becoming the Golden Gophers’ head coach at age 30. The program had not won a Big Ten Championship outright since 1919 and had suffered through five coaches in five years. When asked how long it would take to turn Minnesota into a winner, Musselman replied, “We’ll win right off.”

He delivered. In his first season (1971-72), Musselman led Minnesota to an 18-7 record and the program’s first Big Ten Championship in 53 years. His roster featured future baseball Hall of Famer Dave Winfield, along with Jim Brewer, Ron Behagen, Corky Taylor, Clyde Turner, Keith Young, and Bobby Nix. The Gophers lost to Florida State in the first round of the NCAA Tournament but defeated Marquette in the consolation round.

Minnesota improved to 21-5 in 1972-73, ranking as high as No. 3 in the country. Over four seasons, Musselman compiled a 69-32 record at Minnesota, coached future NBA coach Flip Saunders as a player, and established the program as a Big Ten contender.

The 1972 Ohio State Brawl

January 25, 1972, became one of the darkest nights in college basketball history. During a game between Minnesota (ranked No. 16) and Ohio State (ranked No. 6), a brutal brawl erupted with 36 seconds remaining. Minnesota’s Corky Taylor appeared to help Ohio State center Luke Witte to his feet after a hard foul, then kneed him in the groin and punched him in the head. Ron Behagen stomped on Witte’s head as he lay on the court, knocking him unconscious.

Witte was carried off on a stretcher and hospitalized with 29 facial stitches, a scarred cornea, and a concussion that required 24 hours in intensive care. Two other Ohio State players, Dave Merchant and Mark Wagar, were also hospitalized. Sports Illustrated reported that Winfield “leaped on top of [Mark] Wagar when he was down and hit him five times with his right fist on the face and head.”

Big Ten Commissioner Wayne Duke suspended Taylor and Behagen for the rest of the season. Ohio State coach Fred Taylor, angered that harsher sanctions weren’t imposed, lost his enthusiasm for coaching and retired early in 1976. Critics blamed Musselman’s intense coaching style and pregame frenzy for creating an atmosphere that encouraged violence. A philosophy professor at Ashland College—Wayne Witte, Luke’s father—had previously questioned Musselman’s tactics, telling reporters, “I’m not surprised. Musselman’s intent seems to be to win at any cost.”

Despite the controversy and player suspensions, Minnesota won the Big Ten title with an 11-3 conference record. After Musselman departed for professional basketball in 1975, the NCAA placed Minnesota on probation after discovering more than 100 rules violations, with Musselman named in nearly half of them.

In 2003, Corky Taylor invited Luke Witte, who had become a minister, and Clyde Turner to his home. They watched the video of the brawl, talked through the incident, and called themselves friends from that day forward.

Professional Basketball Career

1. ABA Coaching

Musselman left Minnesota in 1975 to coach the San Diego Sails of the American Basketball Association. According to the book “Obsession” by Bill Heller, Musselman signed a three-year contract worth more than $135,000—considerably more than the $23,000 annual salary he earned at Minnesota. The team folded after just 11 games with a 3-8 record due to financial instability.

One week after the Sails folded, Musselman was hired to coach the Virginia Squires. He went 4-22 before being fired on January 21, 1976. Players worried more about the team’s financial troubles and missing paychecks than basketball, making the situation untenable.

2. WBA and Return to College Roots

In 1978-79, Musselman coached the Reno Bighorns of the Western Basketball Association, leading them to a 28-20 record and the only WBA championship game in league history.

3. NBA Coaching

Musselman’s first NBA head coaching position came with the Cleveland Cavaliers in 1980. The stint was brief and unsuccessful. He was later named Director of Player Personnel for the Cavaliers before being reinstated as head coach.

In 1989, Musselman became the inaugural head coach of the expansion Minnesota Timberwolves. The team finished 22-60 in their first NBA season. While his NBA head coaching record was modest, Musselman’s relentless focus on defense and player development remained evident. In a February 4, 1990 game against the Golden State Warriors, he called the same play repeatedly to exploit matchup advantages, resulting in journeyman center Randy Breuer scoring a career-high 40 points.

4. CBA Championship Dynasty

Musselman’s greatest professional success came in the Continental Basketball Association. In 1983, he coached the Sarasota Stingers but was fired after a 6-13 start. The following season, he moved to the expansion Tampa Bay Thrillers, leading them to three consecutive CBA championships from 1985-1987. The team went 45-18 in 1984-85, 46-19 in 1985-86, and 46-16 in 1986-87 (relocating to Rapid City, South Dakota, for the playoffs).

In 1987, Musselman took over the Albany Patroons and led them to a dominant 48-6 regular-season record and the 1988 CBA championship. This record remained the best regular-season mark in modern CBA history. Several Patroons players—including Scott Brooks, Tony Campbell, and Sidney Lowe—later played for Musselman’s Minnesota Timberwolves. He was named CBA Coach of the Year and earned five CBA All-Star Game coaching selections.

Scott Brooks, who later coached the Oklahoma City Thunder and Washington Wizards, credited Musselman with shaping his career: “One of the things I’ve taken from [Bill Musselman] is doing it every day, being consistent and never changing—always stick with what you do. He was a creature of habit. I wouldn’t be in my position today if he hadn’t taken me on as a CBA player.”

In 1993, Musselman returned to the CBA to revive the Rochester Renegade, a team that had gone 6-50 the previous season. Under Musselman, Rochester improved to 31-25, a 25-win turnaround. The franchise folded after the season.

5. South Alabama and Return to College

In March 1995, after a 25-year absence from college coaching, Musselman took over the University of South Alabama program. In two seasons, he transformed the Jaguars from a 9-18 team into a 23-7 squad that reached the 1997 NCAA Tournament and nearly upset eventual national champion Arizona in the opening round.

6. Portland Trail Blazers and Final Years

On October 7, 1997, Musselman resigned from South Alabama to return to the NBA as an assistant coach with the Portland Trail Blazers under Mike Dunleavy Sr. This marked the first time in his professional career that Musselman served as an assistant rather than head coach.

On October 30, 1999, Musselman suffered a stroke following Portland’s preseason game against the Phoenix Suns. He had served as head coach during the game after Dunleavy was ejected and collapsed after leaving the arena. In April 2000, he was diagnosed with primary systemic amyloidosis, a disease that produces abnormal proteins that collect in tissues and interfere with organ function. He died on May 5, 2000, at 2:45 a.m. at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, from heart and kidney failure. He was 59 years old.

The Trail Blazers used Musselman as inspiration for their 2000 playoff run, which ended in the Western Conference finals against the Los Angeles Lakers.

Coaching Philosophy and Style

Musselman’s coaching philosophy centered on defense, discipline, and maximum effort. He believed strong defense won championships and pushed players relentlessly to reach their potential. His famous quote—”Defeat is worse than death because you have to live with defeat”—captured his uncompromising competitive nature.

The New York Times described his approach: “Musselman claimed ‘the only time I yell is before a game and at halftime,’ explaining that his passion helps players give ‘maximum effort every second.'” Former CBA coach Charley Rosen noted that Musselman possessed an “admirable sense of fairness,” once arguing with referees that they had made unfair calls against the opposing team.

Sidney Lowe, who played for Musselman and later became an NBA head coach, said, “He was very demanding, but he was an excellent coach.” NBA coach Flip Saunders, who played for Musselman at Minnesota, described him as having “great passion in everything he did.”

Legacy and Coaching Tree

Musselman’s influence extended far beyond his own career. His son, Eric Musselman, became an NBA head coach with the Golden State Warriors and Sacramento Kings before moving to college basketball, where he coached at Nevada, Arkansas, and currently at the University of Southern California (as of 2024). Bill and Eric were the first father-son combination to both serve as NBA head coaches.

Numerous former assistants and players under Musselman became NBA head coaches, including:

- Sidney Lowe (Minnesota Timberwolves)

- Tyrone Corbin (Utah Jazz)

- Tom Thibodeau (Minnesota Timberwolves, Chicago Bulls)

- Scott Brooks (Oklahoma City Thunder, Washington Wizards)

- Sam Mitchell (Toronto Raptors)

Musselman coached 24 players who went on to NBA careers and mentored three assistants who became NBA head coaches.

Conclusion

Bill Musselman’s career was defined by contradictions. He was a defensive genius who wrote the book on limiting opponents but also fostered an aggressive playing style that led to one of basketball’s most notorious brawls. He won championships at multiple levels but also accumulated NCAA violations. He inspired fierce loyalty from players and assistants while drawing criticism for his intensity.

The newspaper articles following his death described him as “volatile,” “colorful,” “intense,” and “fiery.” Dr. R. Galen Hanson wrote in The Minnesota Daily, “By far—far and away—the memories I will always have of coach Bill Musselman is that he is one of the most unforgettable people I have ever met: winner, writer, teacher, coach. Always.”

Musselman’s 33.9 defense principles, his CBA championship pedigree, and his coaching tree ensure his influence continues shaping basketball. His story serves as a reminder that coaching greatness can coexist with controversy and that a single person’s passion for the game can create ripples that last for generations.