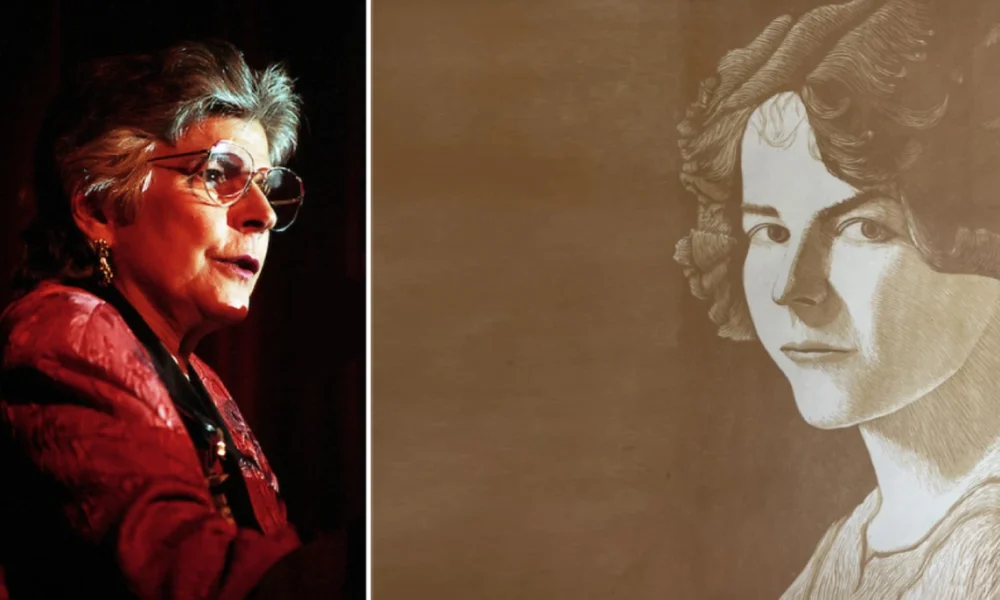

Dr. Helen Rodríguez-Trías: Pediatrician and Women’s Health Justice Advocate

Dr. Helen Rodríguez-Trías transformed women’s healthcare in the United States through her work on reproductive rights, sterilization abuse prevention, and maternal health equity. As the first Latina president of the American Public Health Association, she spent her career addressing how poverty, racism, and inequality affect health outcomes for marginalized communities.

Table Of Content

Born in New York City on July 7, 1929, to Puerto Rican parents, Rodríguez-Trías experienced the intersection of healthcare and social justice from childhood. Her family moved between New York and Puerto Rico during her early years, and when they returned to the U.S. when she was ten, she faced discrimination in the education system. Despite receiving good grades and speaking fluent English, school administrators placed her in classes for students with learning disabilities. Only when a teacher recognized her intelligence was she moved to appropriate coursework.

| Full Name | Helen Rodríguez-Trías |

|---|---|

| Born | July 7, 1929, New York City, New York |

| Died | December 27, 2001, Santa Cruz, California |

| Cause of Death | Lung cancer complications |

| Education | BA (1957), MD (1960) – University of Puerto Rico |

| Specialty | Pediatrics |

| Known For | Reproductive rights advocacy, sterilization abuse prevention, and maternal health |

| Major Positions | First Latina President of APHA (1993), Medical Director of New York State AIDS Institute |

| Awards | Presidential Citizens Medal (2001) |

| Spouse(s) | David Brainin (first husband, divorced), Eliezer Curet, Edward Gonzalez Jr. |

| Children | Four children: Jo Ellen Brainin-Rodriguez, Laura, David, and Daniel |

Education and Early Career

Rodríguez-Trías pursued medicine because it “combined the things I loved the most, science and people.” After graduating from high school, she returned to Puerto Rico to attend the University of Puerto Rico in 1948, where scholarship programs made education accessible.

As a student, she became involved in the Puerto Rican independence movement. When university administrators prevented nationalist leader Don Pedro Albizu Campos from speaking on campus, approximately 6,000 students went on strike. Rodríguez-Trías participated in the protest, which led to her brother threatening to cut off financial support. She temporarily left Puerto Rico, married, and had three children before returning to complete her education.

She earned her undergraduate degree in 1957 and graduated from medical school in 1960. After completing her pediatrics residency at University Hospital in San Juan in 1963, she began teaching at the medical school while establishing Puerto Rico’s first infant health clinic.

- 1960 – Graduated from the University of Puerto Rico School of Medicine

- 1963 – Completed pediatrics residency at University Hospital, San Juan

- Early 1960s – Established Puerto Rico’s first infant health clinic; reduced infant mortality by 50% within three years

- 1970 – Became head of the pediatrics department at Lincoln Hospital in the South Bronx

- 1970s – Founded Committee to End Sterilization Abuse (CESA) and Committee for Abortion Rights and Against Sterilization Abuse (CARASA)

- 1979 – Helped draft federal guidelines requiring informed consent for sterilization procedures

- 1987-1989 – Served as Medical Director of New York State AIDS Institute

- 1993 – Elected first Latina president of the American Public Health Association

- 1990s – Co-director of Pacific Institute for Women’s Health

- 2001 – Received the Presidential Citizens Medal from President Bill Clinton

- December 27, 2001 – Died from lung cancer complications at age 72

Reproductive Rights and Sterilization Abuse Prevention

Rodríguez-Trías’s most significant contribution came through her work addressing forced and coerced sterilization. By 1965, one-third of Puerto Rican women aged 20-49 had been sterilized, often without proper consent. Women were approached during childbirth and pressured to sign consent forms written in English, which many could not read. The procedure, known as “La Operación,” was frequently presented as reversible when it was not.

She co-founded the Committee to End Sterilization Abuse in 1974 and later the Committee for Abortion Rights and Against Sterilization Abuse. These organizations addressed both sterilization abuse affecting women of color and poor women, while also supporting abortion rights for middle-class women who faced different barriers.

In 1979, her advocacy led to federal guidelines that required:

- Written informed consent in a language the patient understands

- A 30-day waiting period between consent and procedure

- Clear explanation that sterilization is permanent

These protections remain in place today.

Work at Lincoln Hospital

When Rodríguez-Trías arrived at Lincoln Hospital in the South Bronx in 1970, the facility served primarily Black and Latino patients and faced criticism for substandard care. That same year, the Young Lords, a Puerto Rican civil rights organization, occupied hospital buildings demanding better treatment for the community.

Rather than dismissing the activists, Rodríguez-Trías worked with them. She trained her staff to understand the social factors affecting patients’ health and encouraged medical professionals to engage with the community. Her approach recognized that poverty, housing conditions, nutrition, and discrimination directly impacted health outcomes.

HIV/AIDS Advocacy

Between 1987 and 1989, Rodríguez-Trías served as Medical Director of the New York State AIDS Institute during the height of the AIDS crisis. She established standards of care for people with HIV, particularly focusing on women, children, and marginalized populations who were often overlooked in early AIDS treatment protocols.

She later led the New York Women in AIDS Task Force, making New York a model for quality HIV care nationwide. Her work ensured that women and children received appropriate treatment and that care standards addressed the specific needs of poor and minority communities.

Leadership in Public Health

Rodríguez-Trías co-founded both the Women’s Caucus and the Hispanic Caucus of the American Public Health Association. In 1993, she became the first Latina president of the APHA, using the position to advance health equity and reproductive justice.

She served on the board of the National Women’s Health Network and contributed to multiple editions of the groundbreaking women’s health book Our Bodies, Ourselves. In the 1990s, she co-founded the Pacific Institute for Women’s Health, a research and advocacy organization focused on improving women’s health worldwide.

Recognition and Legacy

President Bill Clinton awarded Rodríguez-Trías the Presidential Citizens Medal on January 8, 2001, recognizing her work on behalf of women, children, people with HIV/AIDS, and poor communities. She died from lung cancer complications on December 27, 2001, at age 72 in Santa Cruz, California.

In 2018, Google honored her with a Google Doodle on what would have been her 89th birthday. In 2019, New York City announced it would install a statue of Rodríguez-Trías in St. Mary’s Park in the Bronx, near the former site of Lincoln Hospital.

The American Public Health Association established an award in her name. The National Women’s Health Network named its leadership development program after her. Her daughter, Jo Ellen Brainin-Rodriguez, followed her into medicine, becoming a psychiatrist in San Francisco.

Family Members

- Father: Damian Rodríguez

- Mother: Josefa Trías (schoolteacher)

- Siblings: José Damian Rodríguez-Trías, Gladys Adela Hilera

- Spouses: David Brainin (divorced), Eliezer Curet, Edward Gonzalez Jr.

- Children: Jo Ellen Brainin-Rodriguez (psychiatrist), Laura, David, Daniel

- Grandchildren: Seven

Final Words

Rodríguez-Trías believed that healthcare professionals must understand the social conditions affecting their patients. She stated: “I think my sense of what was happening to people’s health was that it was really determined by what was happening in society—by the degree of poverty and inequality you had.”

Her work bridged divides within the women’s movement, connecting reproductive rights activism with broader social justice concerns. She brought together advocates for abortion rights with those fighting sterilization abuse, showing how both issues stemmed from a lack of bodily autonomy and economic power.

Near the end of her life, she expressed her vision: “I hope I’ll see in my lifetime a growing realization that we are one world. And that no one is going to have a quality of life unless we support everyone’s quality of life. Not on a basis of do-goodism, but because of a real commitment—it’s our collective and personal health that’s at stake.”

Her work established frameworks for reproductive rights that recognize women’s need for both access to contraception and abortion when desired, and protection from coerced sterilization. This comprehensive approach to reproductive justice continues to guide advocacy today.